This post should be seen through the lens of working with a team using Git and GitHub during the collaboration of developing software. There is also the assumption that the reader has a firm understanding of Git.

Editing commits are more common than you might think. Anytime you amend, rebase, or squash you are modifying commits, in which the affected commits’ SHA changes.

In a collaborative setting (i.e., a Pull Request in GitHub), we want to minimize editing commits. For many developers, it is worthwhile to keep the Git history as clean and linear as possible. The best way to achieve that simplicity is by reducing multiple commits or rebasing off of master to avoid a merge conflict/commit.

If you are going to edit commits in a collapsing fashion (i.e., amend/squash) in a pull request, make it your last action before merging to avoid confusing code reviewers.

Editing Commits

For brevity, the details of how to edit commits can be found at the following article by thoughtbot. As touched on in my previous post, you can hide the sausage making process by amending and squashing commits. There are two main benefits to consolidating commits:

- The ability to

git bisect,git revertandgit cherry-pickwork without much issue. - Commits are atomic and provide better archaeological information in

git logandgit blamescenarios.

Cautiously Edit a Pull Request’s Commits

As developers learn early on, when a branch is public you avoid carelessly rewriting the commit history. If you do need to get changes from another branch (i.e., master) into the feature branch, there are two options (both which Atlassian covers in great detail):

- The safer way is merging master into the feature branch, which in my opinion makes things a bit messy.

- The cleaner way is rebasing the feature branch onto master, which results in a more linear commit history.

From my experience, I’ve always gone with the rebase option as I value a simplified commit history. Incidentally, the two benefits mentioned in the previous section help with keeping the master branch simple and clean. In practice, this manifests as a final squashing effort before merging the pull request into master.

Regardless, communication is key if you plan to edit the commits of a pull request. Collaborators need to know that they have to account for the rewritten history the next time they want to use or contribute to that branch.

Don’t Edit Commits During Code Reviews

Imagine the following scenario:

- Bob is creating a new feature in his local branch.

- Bob pushes up the branch to GitHub and creates a pull request.

- Bob communicates that he wants feedback from Jane by requesting her as a reviewer.

- Jane makes some comments and good suggestions on the pull request.

- Bob makes changes to address the code review comments.

Now here is where we can hit some diverging paths:

- Bob creates new commits based off the review comments.

- Bob amends the changes onto the last commit.

- Bob squashes the changes into other commits on the branch.

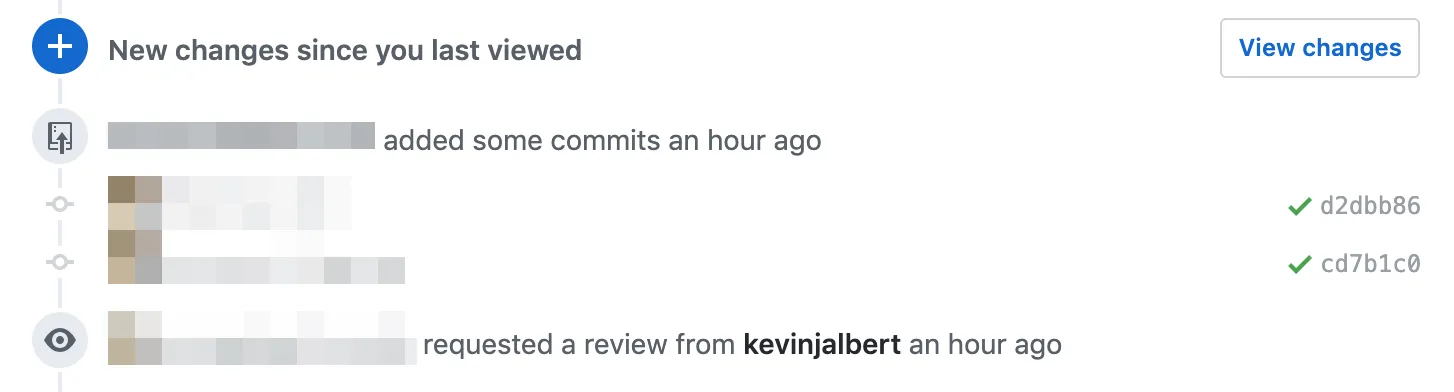

In the three presented cases, Bob addressed the code review comments and the resulting code is identical — only the commits are different. The issue arises when he re-requests Jane to perform a subsequent review. As Jane has already left comments, she instinctively looks to see the new changes on the branch as these changes are more likely the ones that address the earlier code review comments. In the first case, these are represented as new commits, and it is easy enough to see the changes. In the second and third case, the changes are hidden inside previous commits. This makes it incredibly difficult to isolate the changes made since Jane last looked at the pull request.

The take away here is that during the code review phase, we want to ensure that the commits are additive and tell a complete story. A reviewer can and should see how the pull request has changed at each step of the process. The back-and-forth of getting feedback and adding new commits to address them is the collaborative flow for which we should aim.

Squash Before You Merge

Ultimately, we still want that clean commit history when we finally merge, and so we have to squash commits down at some point. As previously mentioned, editing commits during the active code review cycle is detrimental, so you wait until the pull request is approved and ready to be merged.

A final rebase onto master might be needed to resolve any conflicts between the feature branch and master. If we do need this, it’s sometimes useful to get a final check if you were not confident in the conflict resolution.

Ideally, squashing commits results in no code changes from what was already reviewed. If, for whatever reason, there are some changes that need to be made, you’d want some final eyes to check it over. With respect to making the squashing task easier for yourself, I recommend taking a look over the auto-squashing feature built into Git.

It’s worth mentioning that GitHub also has a Squash and Merge option, which does the squashing for you. This is a decent approach if your team is okay with all the changes being compressed down into one commit on master. I personally prefer having the finer grain control over how I structure my atomic commits.

by [haslo](https://flickr.com/people/glodjib) is licensed under [CC BY-NC-ND](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/)'](/_astro/pair-programming.DogRAe41.jpg)