Everyone has preferences in how code should be structured from an aesthetic standpoint. Having creative freedom in finding your own style is a powerful and rewarding feeling. Seeing that new class/file completely written in your style can put a smile on your face. The problem is we’re often not the only developer on a project. In a team or open-source environment, it is unlikely that everyone is on board with the exact coding style. It is not uncommon to see different styles in a project just because everyone has their own.

Why Care?

You might be asking “Why Care?” about styles. As developers, we want to enjoy working in our codebase. If we’re constantly dealing with inconsistent styles, it becomes a mental burden. Also, during code reviews everyone might be imposing their own styles on the reviewed code. After all is said and done, it really comes down to dropping the distractions in a codebase. With a consistent style there are no stylistic arguments in code reviews, and readability increases as the taxing effort of dealing with multiple styles in the same file disappears.

The following is an extreme case of stylistic inconsistencies with two functionally identical code snippets — one follows a styleguide while the other does not.

=begin

This method checks if the two args are equal

it then returns the combined value

=end

def method_one ( first_arg,second_arg )

puts "Executing method_one"

if first_arg.eql? second_arg

puts('first_arg is the same as second_arg')

end

return(first_arg+second_arg)

end# This method checks if the two args are equal

# it then returns the combined value

def method_one(first_arg, second_arg)

puts 'Executing method_one'

if first_arg.eql?(second_arg)

puts 'first_arg is the same as second_arg'

end

return first_arg + second_arg

endHopefully, you found the second snippet more pleasant and easier to read. The second one follows a styleguide while the first one had a mis-match of style.

Starting with Styles

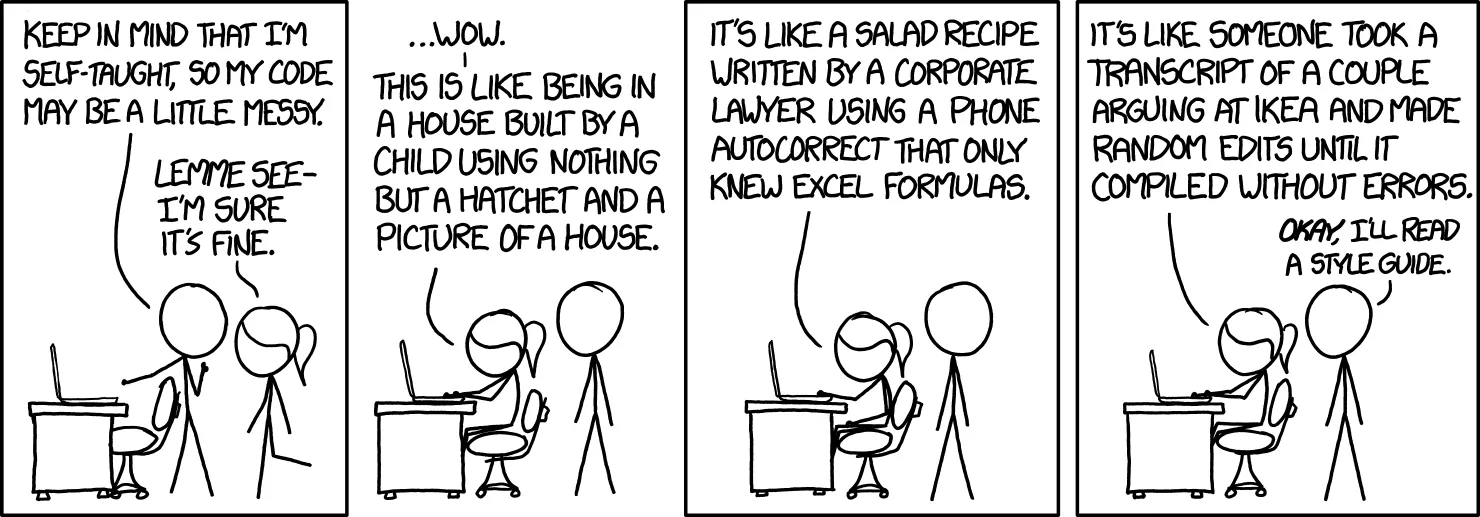

[Image from the EmacsWiki, original comic by Steve Napierski]

Many basic style decisions are made early when a project is started. One of two things happen:

- Styles are implicitly determined by the creator

- Styles are explicitly established upfront by the creator or collaborators

Even if the project starts with an implicit determined style, the end goal is to make it explicit. The more people that contribute to a project, the more chance their coding styles will conflict. Also, your personal coding style evolves over time and it is likely that styles within a project will drift, even with a single contributor.

To reduce wasted time dealing with style issues, just explicitly set a style for your project.

Picking an Explicit Style

I’m willing to bet that all languages have community styleguides (if not, then that’s a great opportunity to start one!). The following are some example styleguides:

- Python - PEP8 Styleguide

- Ruby - Community Styleguide

- Javascript - Airbnb Styleguide

- Javascript - Google Styleguide

When picking a type of style, I recommend to just pick one of the already established styleguides. You might be tempted to start completely fresh and make your own styleguide individually or with other contributors. The problem with creating a fresh styleguide is that eventually there will be the discussion, “I want the style to look like this”, and there will be time wasted trying to make everyone happy (which possibly will never happen). When new developers get started in a codebase they might say, “Why do we have the style like this?”. This leads to a discussion regarding whether or not the styleguide should be revised, which again is a potential waste of time.

You can deflect all styleguide questions if you just select a community styleguide to begin with. These styleguides have already gone through rigorous discussions within the community. One more bonus of using a popular styleguide is that it is likely that other open-source projects are using the same styleguide.

Using Linters

Linters are styleguide checkers that often provide a command line interface and editor integrations. Like previously mentioned with styleguides, there is probably one for each language (if not, what a great opportunity!). The following are some example linters:

A styleguide and linter work hand-in-hand. Together they ensure that code that violates the styleguide is flagged before it is committed to the codebase. There really is no downside to using a linter, and in most cases the benefits far outweigh the effort to set up in your editor. I highly recommend that everyone takes advantage of linters within your editor.

Deviating from the Styleguides

If your team is completely set on having customized styles that differ from a popular styleguide, I would still encourage using one as a base. In an ideal scenario it is possible to use inheritance, where you can then inherit the rules from your choice of popular styleguide. If this isn’t possible, then the next best option is to simply copy the whole guide and use that as your base and make modifications to it.

Each styleguide/linter has their own implementation and handling of their configurations. You will have to explore each and see how to deal with the inheritance. For example, ESLint and Rubocop define how to extend/inherit from other styleguides.

Reduce the Distractions

Using a styleguide and linter, it becomes easy to identify and cut off the distractions of inconsistent styles early. If you can fix stylistic changes as you modify the underlying code, then the future you or your teammates won’t have to deal with it later. In addition, during code reviews everyone knows that all stylistic changes should be taken care of, thus reducing the mental burden.

[Image from xkcd]

Applying to an Existing Project

It’s great that you want to get a consistent style in an existing project. Now comes an important decision, “Do we apply all the style fixes immediately, or as we encounter them?” The answer is situational and many factors can influence what works best for your project and team.

With a sweeping change, a lot of code might be modified, although nothing should be functionally different, as we are just dealing with stylistic edits. This can impact the effectiveness of git blame as the latest commit might simply be “Sweeping Style Changes”, and not the actual commit you were hoping for. Fortunately, there are ways to look deeper into the git log and find the actual content you are looking for (i.e., Git Evolution). With a sweeping change of style fixes, the project afterwards would be in a consistent state of styles.

By fixing style issues as you encounter them, it leaves a lot to interpretation by team members. “Do I fix the whole file when I touch a line within it?”, “Do I only fix styles for the lines I touch?”. In either case the commits will contain two concepts now going forward: feature/bug changes and style changes. Not only does this muddy the usefulness of looking back in the commit history, but code reviews now also contain the style element that everyone has to look at. Overall, the distractions of incrementally dealing with style changes never stop. Even while editing or reading the codebase you will subconsciously see the inconsistent style changes which leads to more distractions.

In my personal opinion, rip the band-aid off and just make a sweeping change of style fixes to put your project in a pristine state. In a legacy system, it might make sense to simply do the incremental approach as it would not be often that one would make changes in the battle-tested system.

TL;DR

- Use a styleguide and linter for any software project to help reduce distractions on styles:

- If possible pick a popular styleguide to avoid arguments/discussions on styles.

- Use a linter in your editor to cut off stylistic distractions early (i.e., before code reviews).

- The sooner a project completely adheres to the styleguide:

- The less stylistic distractions are encountered while reading through the codebase, and

- The less work in keeping up the proper styles.

- If possible, use a sweeping approach to applying style fixes:

- The minimal impact on

git blamecan be resolved with proper tools. - Opposed to using the incremental style of fixes, the distractions are reduced within code reviews and edits.

- The minimal impact on