Level Up Your Commit Messages

A well-crafted message is important for yourself and others — it helps frame the context of what changed and why. It is especially important when you have to look back at old commits to figure out why the code has a certain structure or behaviour.

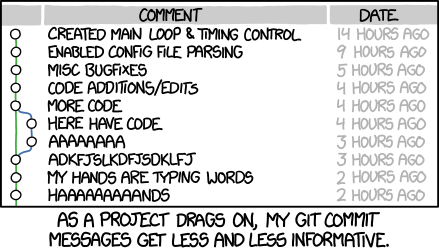

It is easy to make one-line commit messages that have little-to-no context in the description. There are a couple of reasons one might fall into this behaviour:

- Doing exploratory work in which small changes are being made with little care

- Want to move faster (although you will pay for it later)

- Assuming that the why and what are obvious (which it might not be to others)

- Not knowing the value of good commit messages

As the creator of a commit, it is likely you already have a firm grasp of the context surrounding the change. It is not a good assumption that everyone will have the same level of comprehension when they look at your changes. You may also find yourself confused when looking at a commit from several months back if the commit message is lacking context.

Foundation of a Good Commit Message

You cannot talk about how to make good commit messages without referencing these two fantastic posts:

- A Note About Git Commit Messages by Tim Pope

- How to Write a Git Commit Message by Chris Beams

Even though both are referencing Git, the conventions can be applied to any version control system. I highly encourage you to read the above posts (and then come back) to learn what constitutes a good commit message.

As a TL;DR, Chris Beams outlines the seven rules of a great commit message:

- Separate subject from body with a blank line

- Limit the subject line to 50 characters

- Capitalize the subject line

- Do not end the subject line with a period

- Use the imperative mood in the subject line

- Wrap the body at 72 characters

- Use the body to explain what and why vs. how

Commit Early and Often

I learned about the Commit Early and Often approach early in my journey. It is an easy concept to understand, although from experience it can be hard to consistently adhere too. Seth Robertson’s Do commit early and often article explains the benefits:

Git only takes full responsibility for your data when you commit. If you fail to commit and then do something poorly thought out, you can run into trouble. Additionally, having periodic checkpoints means that you can understand how you broke something.

It depends on the person and project, but it is an easy trap to hold your changes and make large commits for the completed piece of work. Seth Robertson raises these concerns but suggests you can hide the sausage making process if you so desire.

People resist this out of some sense that this is ugly, limits git-bisection functionality, is confusing to observers, and might lead to accusations of stupidity. Well, I’m here to tell you that resisting this is ignorant.

Hiding the Sausage Making Process

As Seth Robertson mentions in his note on sausage making, it is the process of doctoring how your final commits look when completed. By committing early and often, the commits will likely expose your complete development process (i.e., fixing a bug you introduced earlier, adding tests after the fact, etc.).

Some people like to hide the sausage making, or in other words pretend to the outside world that their commits sprung full-formed in utter perfection into their git repository. Certain large public projects demand this, others demand smushing all work into one large commit, and still others do not care.

With version control systems, it is possible to edit the commit history. Seth Robertson dives deeper into this in his article on Post-Production Editing using Git. There is another benefit other than the vanity aspect of making a set of commits look good. By squashing bug fixes or even half-baked solutions into cohesive commits that compile and/or pass tests, you are able to git bisect, git revert and git cherry-pick without much issue. In addition, you are able to squash several commits into logical atomic commits — then code review is straight-forward.

Personally, I like to commit early and often, and only after the fact will I squash commits down into atomic commits. These commits ideally are valid from a testing/compiling perspective. The whole set of commits that I push up for code review tell the story of what was changed and why it was done.

Semantic Commit Messages

As an experiment, I’m going to be trying out semantic commit messages (aka conventional commits). The idea here is that commit messages are structured so that it is easy to understand the intention and impact of a commit. In addition, adhering to a consistent format gives commit messages a machine-readable meaning.

The following snippet from Jeremy Mack best illustrates how semantic commits are formatted:

feat: add hat wobble

^--^ ^------------^

| |

| +-> Summary in present tense.

|

+-------> Type: chore, docs, feat, fix, refactor, style, or test.

An optional aspect you can add is a scope after the type to indicate the section of the codebase that the commit interacts with (i.e., fix(linter): fix off by one in main loop). The following is an example of what a commit history with semantic commits might look like:

* bc0ee40 - (2 days ago) chore: bump Rails version

* 52f87c0 - (3 days ago) docs: enhance README documentation

* 66fd6f7 - (4 days ago) feat(payment): add new payment option

* 3f0746c - (5 days ago) fix(admin): bug in dropdown selector

* 2b56812 - (6 days ago) refactor(jobs): background job logging

* da75ea2 - (7 days ago) style: remove extra whitespaces

* 3ade674 - (8 days ago) test(payment): add more tests around payment

The above history is easy to understand, and I believe it’ll help with creating those atomic commits. As mentioned, the commit messages become machine-readable and this paves a way to use tools like semantic-release.

Putting It All Together

To better integrate semantic commit messages into my workflow, I have the following set as my .gitmessage template (learn how to use this in this article by Matt Sumner):

# <type>(<scope>): <subject>

#

# <type> - chore, docs, feat, fix, refactor, style or test

# (<scope>) - optional, section of codebase involved

# <subject> - present tense summary, whole line is 50 characters

#

# 72-character wrapped longer description. This should answer:

# * Why was this change necessary?

# * How does it address the problem?

# * Are there any side effects?

#

# Include a link to the ticket, if any.

#

# Add co-authors if you worked on this code with others:

# Co-authored-by: Full Name <[email protected]>

As always, keep on levelling up!