Respect HTTP Caching

API developers place plenty of consideration on how to handle scaling. A few techniques and approaches: Application caching, sharding, larger/more servers, background queues, HTTP caching, and Content Delivery Networks (CDNs). A well architected API employs a combination of these solutions to achieve the desired scalability. Of the scaling solutions, very few are actually exposed to the consumers of an API. One strategy in which the end-users actively participate in is HTTP Caching.

By respecting HTTP caching on a client’s application, network communications complete quicker and in some cases are unnecessary. Network response payloads are sometimes omitted due to a 304 HTTP response. Finally if you use HTTP caching, application servers will love you.

HTTP Caching

If an endpoint is to be hit repeatedly, HTTP caching can dramatically reduce the load on the server. There are a number of ways one can use HTTP caching. Similar to other scaling techniques some of these can be used in tandem.

Cache-Control

On an HTTP response a cache-control header may present. This header provides the client insight on how they should approach making similar requests. For example:

Cache-Control: max-age=60, must-revalidate

The max-age=60 specifies that the request should be cached and used locally for a maximum duration of one minute. The must-revalidate forces subsequent requests to still communicate to the server to respect the freshness of the response (i.e., information which indicates that the content of the response has updated). These two simple cache-control headers provide both non-stale responses with reduced payload, provided the endpoint is respecting the max-age (i.e., not changing frequently).

To better understand cache-controls, our coworker at theScore, Thuva Tharam, has an excellent blog post written on the subject. The individual cache-control directives and their effects are described. Suggestions and examples are provided to illustrate how to use cache-control effectively.

Last-Modified

As previously mentioned, it is possible for a cached request to re-validate with the server to check for freshness. Subsequent requests have an additional If-Modified-Since which contains the value of the response’s Last-Modified header. This allows the server to compare the provided time on subsequent requests against the responses and return the full response or simply a 304 status code.

When a server returns a full response it takes more time to compute/collect the necessary information along with rendering time for the response. With the correct cache-control along with a Last-Modified, a server spends less time constructing the response. A 304 status code response is quick, and has a small payload size compared to a normal full response.

ETags

Even when the Last-Modified value has changed, the actual content might still be the same. If the server takes advantage of ETags then there will be an ETag header on the response. The benefit of using ETags shines on requests that do not change often. ETag caching does not expire based on time like the previous two caching mechanisms, and is instead a function of the response’s content. This form of caching is ideal as it provides caching while still allowing for freshness of updates to the content.

When a subsequent request is made a If-None-Match header is sent along with the previous request’s ETag. The server will then use the ETag to determine freshness. If the ETag of the request match the that of the server’s response a 304 status code is returned.

Respecting HTTP Caching for API Consumers

API Consumers – Client applications that makes more than one HTTP request to an external web service

API Consumers can take on different forms such as a browser or desktop/mobile/web application.

Browsers

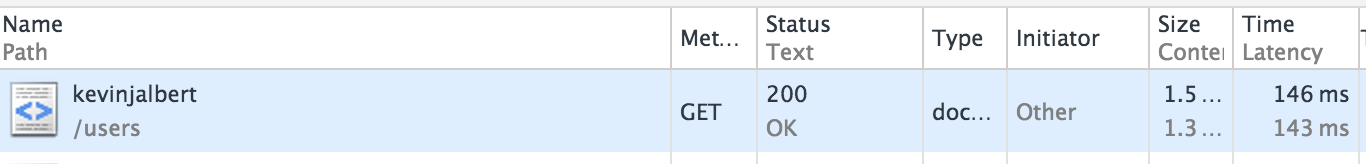

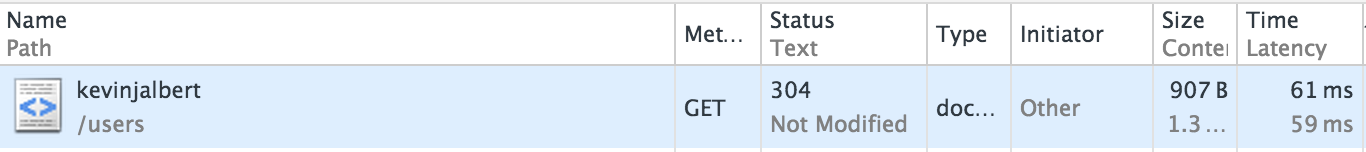

Modern browsers have no problem handling HTTP caching. It is also easy to verify that they are respecting HTTP caching by using their Developer Tools interface. The following image shows two requests made to the same API endpoint (https://api.github.com/users/kevinjalbert) in Google Chrome’s Network Tab of the Developer Tools:

First API request results in a 200 status code (standard success response):

Second API request results in a 304 status code (resource has not been modified since the last request, no body is returned in response):

Mobile Applications

Android and iOS have native mechanisms in place that developers can use to handle HTTP caching on any outbound requests. On iOS there is NSURLCache and on Android there is HttpResponseCache. If possible all HTTP requests made from mobile devices should be using the caching mechanisms.

Desktop Applications

Many programming languages can be used when creating desktop applications. In these cases it is best to check whether there is a built HTTP request caching mechanism akin to what Android and iOS have.

Web Applications

It is not uncommon to have web services talking to other web services through a defined API. In these situations there might not be a defined networking layer to push API requests through. For example, within a Ruby/Rails application one might use Faraday to handle network connections. HTTP caching is not enabled by default on Faraday and is instead an opt-in option.

The following is an example of using Faraday with Faraday::HttpCache middleware to handle HTTP caching.

require 'active_support'

require 'faraday'

require 'faraday-http-cache'

module ApiConsumer

class Requester

def initialize(cached: true)

@connection = Faraday.new('https://api.github.com/') do |conn|

if cached

conn.use Faraday::HttpCache,

logger: Logger.new(STDOUT),

instrumenter: ActiveSupport::Notifications

end

conn.adapter Faraday.default_adapter

end

end

def get(method, params = {})

start_time = Time.now

response = @connection.get do |request|

request.url(method, params)

end

time_taken_ms = (Time.now - start_time) * 1000

puts "Time Taken: #{time_taken_ms.round(3)} ms"

response

end

end

end

# Subscribes to all Faraday::HttpCache events

ActiveSupport::Notifications.subscribe "http_cache.faraday" do |*args|

event = ActiveSupport::Notifications::Event.new(*args)

puts "Cache Status: #{event.payload[:cache_status]}"

end

puts "Faraday with HTTP Caching"

api_requester = ApiConsumer::Requester.new(cached: true)

5.times do

api_requester.get('users/kevinjalbert')

sleep 2

end

puts ''

puts "Faraday without HTTP Caching"

api_requester = ApiConsumer::Requester.new(cached: false)

5.times do

api_requester.get('users/kevinjalbert')

sleep 2

end

Executing the above example produces the following log statements. With caching the time taken per request decreases tremendously on subsequent requests. By respecting the HTTP cache-controls of the API, the subsequent request can be used until the cache-control directives say otherwise (i.e., ETag/Last-Modified changes, or the cache expires exceeding the max-age).

Faraday with HTTP Caching

D, [2015-09-20T23:06:27.570751 #15189] DEBUG -- : HTTP Cache: [GET /users/kevinjalbert] miss, store

Cache Status: miss

Time Taken: 1396.139 ms

D, [2015-09-20T23:06:29.577798 #15189] DEBUG -- : HTTP Cache: [GET /users/kevinjalbert] fresh

Cache Status: fresh

Time Taken: 1.857 ms

D, [2015-09-20T23:06:31.580719 #15189] DEBUG -- : HTTP Cache: [GET /users/kevinjalbert] fresh

Cache Status: fresh

Time Taken: 0.971 ms

D, [2015-09-20T23:06:33.585455 #15189] DEBUG -- : HTTP Cache: [GET /users/kevinjalbert] fresh

Cache Status: fresh

Time Taken: 1.139 ms

D, [2015-09-20T23:06:35.587833 #15189] DEBUG -- : HTTP Cache: [GET /users/kevinjalbert] fresh

Cache Status: fresh

Time Taken: 1.133 ms

Faraday without HTTP Caching

Time Taken: 807.486 ms

Time Taken: 277.589 ms

Time Taken: 186.115 ms

Time Taken: 475.249 ms

Time Taken: 1130.691 ms